Buckminster Fuller today

ho

A conversation with curators Rosa Pera and José Luis de Vicente about the exhibition «Radical Curiosity. In the Orbit of Buckminster Fuller».

Reviewing the legacy of such influential figures as Buckminster Fuller is a highly complex exercise, but also an opportunity and a challenge that curators Rosa Pera and José Luis de Vicente had long had in mind. We have interviewed them about the exhibition that they are about to present around this unclassifiable architect/designer/thinker, entitled «Radical Curiosity. In the Orbit of Buckminster Fuller». It was meant to open on March 25th at Espacio Fundación Telefónica de Madrid but Spain’s national lockdown measures to stop the expansion of Covid-19 put the opening on hold.

Do you have a new opening date?

Rosa Pera (RP) – In autumn, probably September.

How did the idea of an exhibition around Buckminster Fuller take shape?

José Luis de Vicente (JLDV) – It emerged in conversation with Fundación Telefónica. They had made a series of exhibitions dedicated to important figures such as Tesla or Jules Verne with the aim of creating a collective imaginary around the relationship between society, technology and innovation today. Rosa and I, in parallel, had been for several years, and at various times, interested in Buckminster Fuller.

For me personally, it had always been a kind of reference that had exerted a fascination on many subsequent generations of the kind of work I am more aligned with; and Rosa, at that time, was also investigating a series of topics that had led her to him.

RP – I was researching issues related to informal education, and how creation in art and culture are enmeshed in a more innovative way. Somehow I got to Fuller and began to further investigate his legacy. Sharing these ideas with José Luis, we thought it was a good time to recover his figure now. Buckminster Fuller had somewhat anticipated many of the problems we are experiencing today, such as the current climate emergency and the need to radically reformulate systems. For this reason, we decided to present the exhibition project to the Espacio Fundación Telefónica. It fitted with the programming line of the space, with our research, and with many of the challenges that we are dealing with today.

How would you present Buckminster Fuller to people who have not heard much about him?

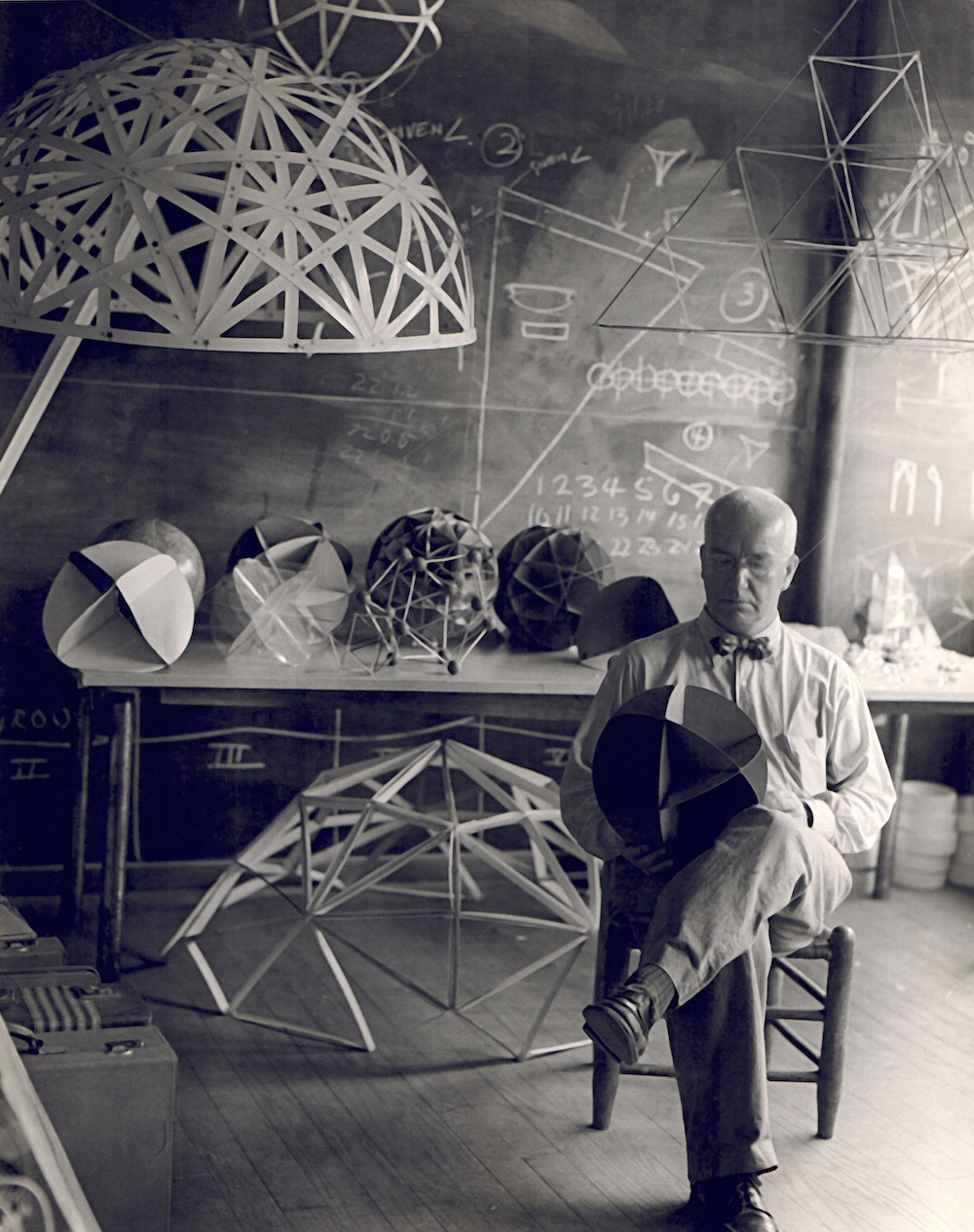

RP – He was a visionary of the 20th century with ideas of the 21st century who brought bold new perspectives in areas such as architecture, design, education and the relationship of the inhabitants of the Earth with the planet and the universe.

JLDV – For me, what is most remarkable for someone who does not know Fuller is that, in the 21st century, we have naturalized that in our cultural environment, the traditional barriers between art, thought, design and science are fluid, and that all processes contain elements from everywhere. This has not always been like that. This process had a historical beginning, a start, and the figure of Fuller was essential to catalyze this sort of ideas and processes and to demonstrate that the limits between a philosopher, a designer, an architect and an inventor are not rigidly fixed.

How would you, on the contrary, present him to whoever thinks they already know everything about Buckminster Fuller?

RP – I would say that Bucky is unreachable; his universe is like one of his dodecahedra, covered in mirrors and in permanent motion. Depending on the light in which it is lit, it can spark different reflections and different perspectives depending on the time.

JLDV – It seemed to us that his figure in Spain is obviously very well known in the fields of design and architecture, but not necessarily for the general public. That is why we thought it was very interesting not only to talk about Buckminster Fuller and his importance, but to talk about him in 2020 and in relation to contemporary artists, designers and architects. Having been born and raised at a time of transition from the 19th-century to the 20th-century world, Fuller thought about and anticipated the systemic problems of the 21st century. He was the first to look at the inherent limitations of growth, of the idea that growth would clash with the biophysical limits of the planet.

Yes, his figure is very well-known in the fields of architecture and engineering, but his ideas go much further… What is his most remarkable legacy for you?

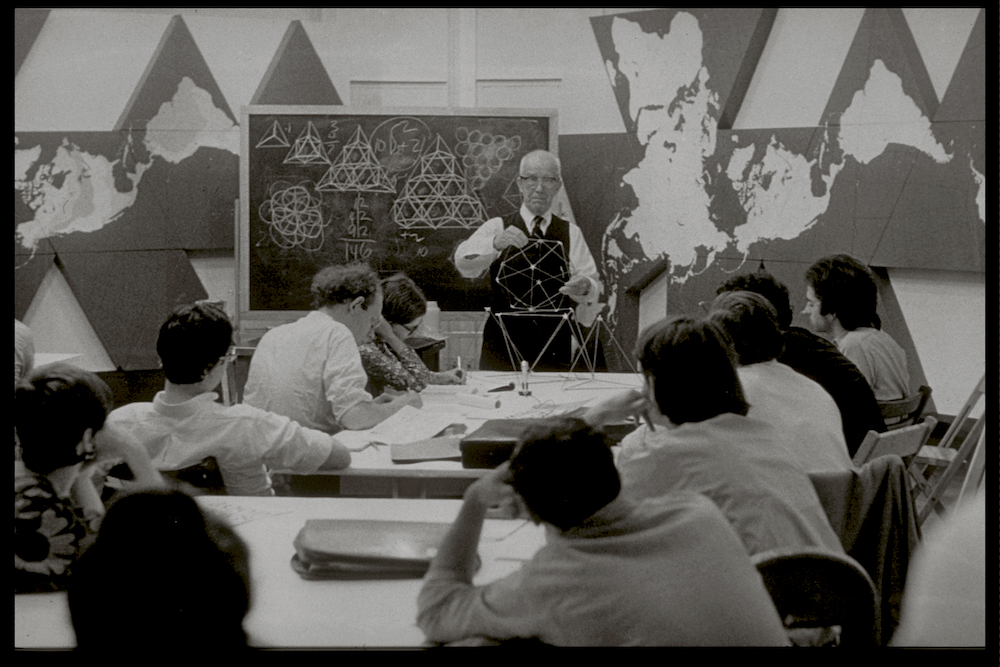

RP – Something that defines Fuller a lot is overflow. When he lectured, his discourse overflowed. If you listen to his lecture series «Everything I know» you see that they ask him a question and he starts at one point and suddenly he begins to develop a whole universe that leaves the initial theme and ends up being even more interesting. It overflowed all formats, both the conference and the book, which is seen in the publications he made.

This is one of the most positive and useful aspects to keep in mind of Fuller’s legacy, that things do not start and end in themselves. On the one hand, he spoke of the notion of synergy, which he applied to all the research, theories and devices that he generated. With it, he meant that it makes no sense to focus on one part because the whole is explained by the interaction of the parts. He himself was very consistent and his head was totally synergistic, and his way of communicating was too, and that’s super interesting.

On the other hand, the idea that the world can work differently and that anyone can change it by thinking and acting is also one of his most important legacies. One of the most interesting quotes by him around this reads: “Never change things by fighting against existing reality. To change something, create a new model that will make the existing model obsolete”.

One of the most appealing things about any exhibition is how it can create a dialogue with the current moment and it seems that in the case of Buckminster Fuller this dialogue is extreme. You say that he was a personality of the 20th century operating with ideas of the 21st century. What were some of these ideas that would particularly resonate today?

RP – For example, that the Earth’s resources are finite, that how to manage them is key and that big data is a good way to do it. This seems very obvious now, but he stated it a long time ago: that one had to look at the processes of nature to find the same system that would govern the planet and today’s society.

He would also argue that there is no sense in an epistemological system based on specialization and tight disciplinary categories. On the contrary, what is most effective and natural is to think and work in antidiscipline, in the fertile territory between disciplines and academic categories. He was one of the forerunners of the debate around organising knowledge by disciplines and anti-disciplinary thinking. He believed that specialization was a mistake and that the most important thing is the connection of knowledge through research and experimentation. In this sense, Fuller advocated for reimagining education entirely, and his proposal that universities should stop for a decade to dedicate themselves exclusively to thinking about how the world could work differently is quite famous. Today it is usual to work in projects and workshops based on practice and interdisciplinarity, multidisciplinarity or even antidisciplinarity (as in the case of the MIT), and all of this is something Fuller already raised at the time. He worked simultaneously with artists and scientists in a very natural, almost militant way. Someone who exemplifies this perfectly today is the artist and researcher at the MIT Neri Oxman, present at the exhibition.

JLDV – Another of the big issues that Buckminster Fuller addressed and to which he devoted the first part of his career was that of affordable housing, a problem that remains unresolved today. When we were talking about the exhibition, it was evident that all the big cities in the developed world were experiencing a housing crisis and that the lack of affordable housing is still what determines people’s life chances the most.

RP – In fact, the problem that society has with housing is the tip of the iceberg in which the system that has brought us here is based, which is property. And that was exactly one of the issues that Fuller questioned: to have a home you do not have to own the land because a home can be light and mobile and should not depend on land ownership.

JLDV – Another fascinating topic that resonates a lot for me, that I have dedicated more than fifteen years to investigating the space of relation between technology and society, is Fuller’s technodeterminism: he thought that there was no problem, the solution of which was not technological. In fact, you can create a very clear genealogical line between how Fuller’s ideas impact the counterculture and the “hippies” movement, which is one of the values that defined California’s society when it began to forge the relationship model between alternative lifestyles and emerging industries (such as that of computers, which created the breeding ground that would become Silicon Valley). Fifty years later, somehow, this mentality that all problems have a technological solution, that we do not need political solutions or political agreements where we can find a technical solution, has created a very specific model of the world that some call solutionism. By this, I mean that there is also a dark side or pernicious influence on Fuller’s figure that is very interesting as well. In fact, Fuller also created, in a way, the prototype or origin of the inspirational speaker who believes in triumphalist speeches to find the utopia of better worlds where there are no winners or losers but we are all the same. In short, for me, what is really fascinating is that, for better or for worse, we are still living under the shadow of Buckminster Fuller in 2020.

The exhibition is titled “Radical Curiosity. In the Orbit of Buckminster Fuller.” Who is in this orbit?

RP – We say in the orbit of Buckminster Fuller because we present him accompanied by an exciting selection of contemporary artists, designers and architects who act picking up some of the ideas and strategies that he put on the table at the time. But we also highlight this orbit because we wanted to avoid paying a eulogy to his figure and we preferred to show his lights and shadows and the impact his ideas have had. We present him because he is not such a well-known figure in Spain as he is in the United States (outside the most specialized fields of design and architecture), but we also believe that it is important to explore how we should look at him and absorb his ideas right now from a critical vision of our present.

For example, it is quite surprising how he is claimed as a great reference both from Silicon Valley and the hippie movement. Or how he wanted to apply the ideas of Fordism to housing so that everyone could access it and there would be no inequalities or any prejudice for the planet and sustainability, but Fordism has precisely been the basis of capitalism that has taken us where we are. These tensions seem very interesting for us to explore through his figure and also through his environment and through the people that have continued to explore what he had already considered.

In his orbit, at his time, we could find names such as the sculptor Isamu Noguchi, Steward Brand or the architects Cedric Price and Norman Foster. Today we can find artists like Olafur Eliasson or designers who have been inspired by his ideas and observations, such as those who work taking nature as the main source of knowledge, such as Neri Oxman, Joris Laarman or Tomas Libertiny, or architects like Andrés Jaque. We are also very interested in his speculative and more art-related side, which we have included in the exhibition with references to the architect Jose Miguel de Prada Poole or the artist Gyula Kosice.

JLDV – Another of the most fascinating things about Fuller is that he is a very difficult figure to locate ideologically speaking and this is also reflected in the impact he has had. In some cases, he was an extreme believer in large-scale macro-production and in the mechanisms of capitalism to be able to distribute at all levels, but on the other hand, he also defended measures in many cases almost radically left-wing regarding property. Libertarian measures not only in terms of individual rights, but that pointed towards radically abolishing principles of the market society. When we talk about his orbit we also come across these paradoxes. If you see the architects who have followed him, there are his direct disciples such as Norman Foster (with whom he collaborated and had a personal relationship) who is one of the architects who most exemplifies the power of architecture to represent capital; and on the other hand, ecological architects like William MacDonough or Shigeru Ban also admit much the weight of his ideas. All this makes him a figure that is endless in scope…

For some people, if this exhibition had been held 10 or 12 years ago, perhaps it would have explained Fuller’s work almost as a series of beautiful utopias that ultimately failed because most of his projects were not very successful beyond the geodesic dome. What is left are prototypes and stories of failures: the car that was going to revolutionize the market but failed, the mass-produced houses that were never manufactured… However, if we consider that in 2020 the most recognized architect and artist in the world are Norman Foster and Olafur Eliasson, and that in both cases, Fuller’s influence is more than evident, it is very difficult to speak of his career in terms of failure.

RP – Yes, also the last Milan Design Triennial, curated by Paola Antonelli under the title «Broken Nature. Design Takes on Human Survival» started with a quote from Buckminster Fuller. That a reference exhibition like this, which wants to appeal to new relationships with the planet to invent more sustainable futures, makes such an explicit reference to Bucky is no coincidence.

How have you translated all these to the exhibition layout, and also in terms of graphic and exhibition design?

RP – We have organized the exhibition into eight thematic axes, all connected to each other: Make your life an experiment, Revolution Design, Shelter, Tensegrity, Experimentation, Geodesy, Information and Education. The life, ideas and inventions of Fuller run across these axes overlapping with the work of other designers, artists and architects of his time and today. Together, they offer a network of ideas and visions that are interconnected and inspiring for a present full of uncertainties and a world that requires profound changes.

We have approached the exhibition based on concepts rather than specific displays, which has had difficulty since everything was connected in some way. Buckminster Fuller has a spherical and geodetic way of thinking so we have organised the exhibition in a circular way.

We also want to highlight a display we have commissioned to Studio Folder to deal with the concept of information. This is the only section where the thickness is the work of these contemporary designers, who have departed from Fuller’s references and materials. In the rest of the sections, the exercise is inverse.

The graphic design has been created by Opisso and we have worked on the design of the space with Fernando Muñoz Gómez, who knows the venue very well. We were very clear that we did not want a traditional white cube exhibition space, we wanted a space that transmitted Fuller’s spherical and synergistic way of thinking, where everything was connected, and so we suggested that this should be reflected in the entire experience, including the graphic and exhibition design.

JLDV – Something we have noticed throughout these the two years of research that the project has taken, is that we have been working with sixty years of work by someone who was absolutely hyperactive and excessive. A thousand different exhibitions could be made about him!

RP – Yes, one of the great challenges of the exhibition has been how to present the Dymaxion Chronofile, the entire Fuller’s archive that is at Stanford University. In 1927, after a great crisis, Fuller decided to start keeping all the documents that went through his hands. The result of this decision is that large-volume archive in which we immersed ourselves when we were researching and that we wanted to communicate to the visitor. It somehow represents his unattainable universe. That is why the exhibition begins with an immersive installation of the Dymaxion Chronofile. It seemed to us the best way to represent the Fuller spirit, to immerse ourselves in his head.

I imagine that you have had to rethink the public program. What has remained and how will the programme be able to reach audiences beyond Madrid?

RP – The programme will be available online. At the moment, there is a Spanish podcast series made by PodiumPodcast called «Curiosidad Radical Fuller» and we have launched the initiative «The Fuller Educational Challenge», designed by the team at Espacio Fundación Telefónica together with the Ashoka Foundation, dedicated to social innovation. It aims to bring together external educational organizations connected with different social realities.

The Fuller Educational Challenge is a contest aimed at the participation of young people between 14 and 18 years old around innovation, education, sustainability, technology, design, etc., Through the figure of Fuller, educational centres of secondary education, vocational training, baccalaureate, non-formal education entities or independent youth groups are invited to experiment. The young people, organized in teams, can participate in by proposing projects that, through the use of technology, revert benefits for society as a whole. Now it is active online, through the Creating for Humanity initiative, a global call to young people from large institutions to create projects and come up with ideas that can contribute to improving the post-Covid-19 world. The public programme will continue face-to-face in the fall.

In anticipation of the exhibition, do you recommend any of his books or a podcast or movie about his ideas?

RP – Yes, we recommend the podcasts that speak about the exhibition and Fuller’s figure, they are informative. For a deeper understanding, we recommend the book «Buckminster Fuller. Anthology for The Millennium» edited by Thomas Zung, architect and one of Fuller’s closest collaborators. The book contains a selection of Fuller’s writings, each introduced by great Bucky connoisseurs, such as Norman Foster, Arthur C. Clark or E.J. Applewhite. The famous collection of lectures by Fuller «Everything I Know» is also very interesting. They are the result of a marathon of 12 talks that he gave in 1975 and that lasted 42 hours. Many of the sessions are online and are exceptional material to get closer to the Fuller universe first hand.

Interview: Sol Polo