From Mrs. Pollock to Lee Krasner

ho

A retrospective at the Barbican in London pays tribute to the work of the American abstract expressionist who was the wife of Jackson Pollock.

The art of Lee Krasner is finally getting the attention it deserves with a major retrospective at the Barbican Centre in London, the first in Europe for over 50 years. Navigating it makes me wonder how many more art histories are we missing having overlooked artists like her for so many years.

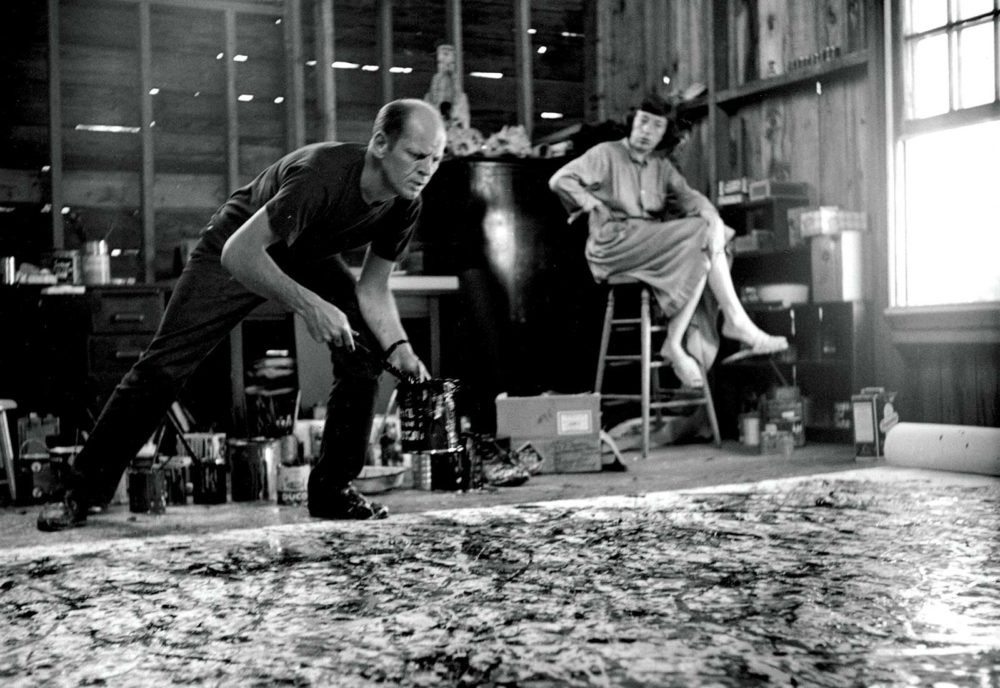

Krasner was better known for being Jackson Pollock’s wife than for being an artist, even though she was painting “before, during and after Pollock” – as she claimed – and created an outstanding body of work for over six decades, from 1920’s to the 1980s, constantly evolving her style to express her inner voice. Seeing the evolution of her career as it is shown at the Barbican is fascinating: it shows her determination to be an artist in times where women weren’t even accepted in many art schools, her outstanding craft as a painter, her ability to experiment with techniques and materials and to explore the shifts of her inner voice.

Indeed, her inner voice speaks out in many ways, but it also conceals so much, which makes it exciting to navigate: “My work is so autobiographical if anyone can take the trouble to read it”. From the smallest watercolour to the floor to ceiling canvasses she made when she moved her studio to what had been once Pollock’s territory, her changes of scale, style, color palette and rhythm say a lot about her passioned artist soul: “You can have a small canvas that is monumental in scale” she stated, but they also reflect her love for jazz, improvisation and experimentation. Krasner used to dance swing in the 40s in New York, but she preferred dancing with Mondrian because Pollock step all over her.

This passion is very present in her work and it is also quite revealing as a mechanism to process the multiple struggles she had to overcome: from teachers drawing on top of her work to tutors telling her that her work was so good nobody would believe it was the work of a woman, to adjusting her practice to the constraints of a domestic space to leave the big studio to Pollock, to bearing with Pollock’s mistresses and alcoholism problems, having to mourn his sudden death in a car accident and overcoming the grief to deal with his legacy and keep on with her life and work, which she regarded as one.

It is delightful to see the multiple references in her work (Picasso, Mattisse, Kandinsky, Miró, Russian Constructivism…) and how her style changes so much over time, something which at the time came across as a lack of signature style, something that utterly bothered her: ““I have never been able to understand the artist whose image never changes. (…) All my work keeps going like a pendulum; it seems to swing back to something I was involved with earlier, or it moves between horizontality and verticality, circularity, or a composite of them. For me, I suppose, that change is the only constant.”.

The exhibition also speaks to a variety of audiences, not only an art audience. Architects will be delighted by the grandness of the exhibition space, designed by David Chiperfield, and host inside one of London’s brutalist gems, but also by Krasner’s constant shift of scales and architectural sense of composition. Musicians and dancers will get lost in the rhythms and modulations of her brushwork. Designers will enjoy her use of bold colours, the richness of forms and patterns, her experiments with furniture design, her ability to go back, destroy, re-use and clarify, and her work for the War Windows Service, where she combined collage, painting and typography and experimented with collective authorship and vitrine design. There is also a mention to another fellow women artist, Ray Eames, which was a close friend of Krasner and beautifully documented her studio and her surroundings in a series pf pictures that are included in the exhibition as a backdrop. How the Eames built a shared legacy as a design couple and the Pollock’s didn’t also says a lot about how different designers and artists operate.

But the exhibition is not only surprising because of the depth, breadth and strength of her work, personality and environment, brilliantly expanded with an epic closing video edit of different interviews she gave towards the end of her career when her work started to get attention from the first wave of feminists, but because it is difficult to cope with the fact that this strong work and personality didn’t get hardly any recognition until very recently.

I took an art history course led by a recognised scholar specialised in abstract expressionism and he never mentioned Krasner. Many art world savvies attending the show these days had never heard from Lee Krasner before. It wasn’t that she was a shy personality, quite the contrary, and it was her who introduced Pollock to Peggy Guggenheim, the powerful art collector that would boost his career over hers, or the critic Greenberg, who would decide who would make it into the history of art (Pollock) and who wouldn’t (Krasner), and ironically, it was also her who contributed to keep the legacy of Pollock alive. But it seems like all she really cared about was her art, she was too busy with it to get distracted seeking any credit or reassurance, and that, for better or for worse, has gifted us with this groundbreaking discovery, which hopefully will encourage audiences to ask for more.

Author: Sol Polo