Living the process and capturing the ephemerality behind creation

ho

We visited Glithero (Sarah Van Gameren and Tim Simpson) in their London studio to get some insights on their work.

Dutch and British design duo Sarah Van Gameren and Tim Simpson, a.k.a. Glithero, are not new to the design scene. They have been running their studio for over 10 years now, but their work feels as fresh and unique as it was when they started.

In 2015, their Silverware vases travelled to Barcelona to be part of our exhibition Out of Place, for the way they integrated a photographic process within a product, and Tim gave an epic keynote where he spoke about their obsession with process through a youtube video of the making of a Vienneta ice-cream. Their particular approach to process, nevertheless, is the opposite of industrial, and focuses instead on performance, craftsmanship, harvesting and transformation.

All their works deal with how to make visible a process that it is often invisible, especially in design. We talked to them in their studio in North London, where they shared some insights to their particular design process and what drives every single project they take on.

You have recently launched Botanical Tiles, which seem like a sister project to the Blueware Tiles and a cousin of the Silverware and Blueware vases you exhibited here at FAD in 2015. Can you tell us a bit more about the project and how are they connected?

Yes, they are related. We love to evolve our projects sometimes. We have always been interested in plants. One of the first projects we did as a studio came out of an archive of botanicals we started, a herbarium. Every year we harvest new plants. Sometimes we go for seaweeds to the coast, but most of the time we work with plants that are really local to us, that we find on the surroundings of our studio. Over time we have found out that when you create a herbarium, the least interesting plants are the ones that look good on the shop. We are not that much interested in those ones, but more on the urban ones. We capture them, carefully flatten them and dry them over a couple of months and then we start using them.

We used them for the UV printed collections or Blueware vases, our ceramics printed with cyanotype photographs. We later developed the project with silver printing photography on porcelain, which became the Silverware collection. For the Botanical Tiles, we came across a tile atelier in the Netherlands where they showed us techniques they have been using in the past. Most of them are not used any more and they were keen to bring them back. We found a really good method, which looks like a blueprint. With it, there is an interpretation of the specimen, which is hand drawn, and this makes every piece really unique. We could develop this project because a client of ours that has been following our work for a long time commissioned us the first panel and now we are already working on our 6th mural!

Can you tell us a bit about the Nez a Nez project?

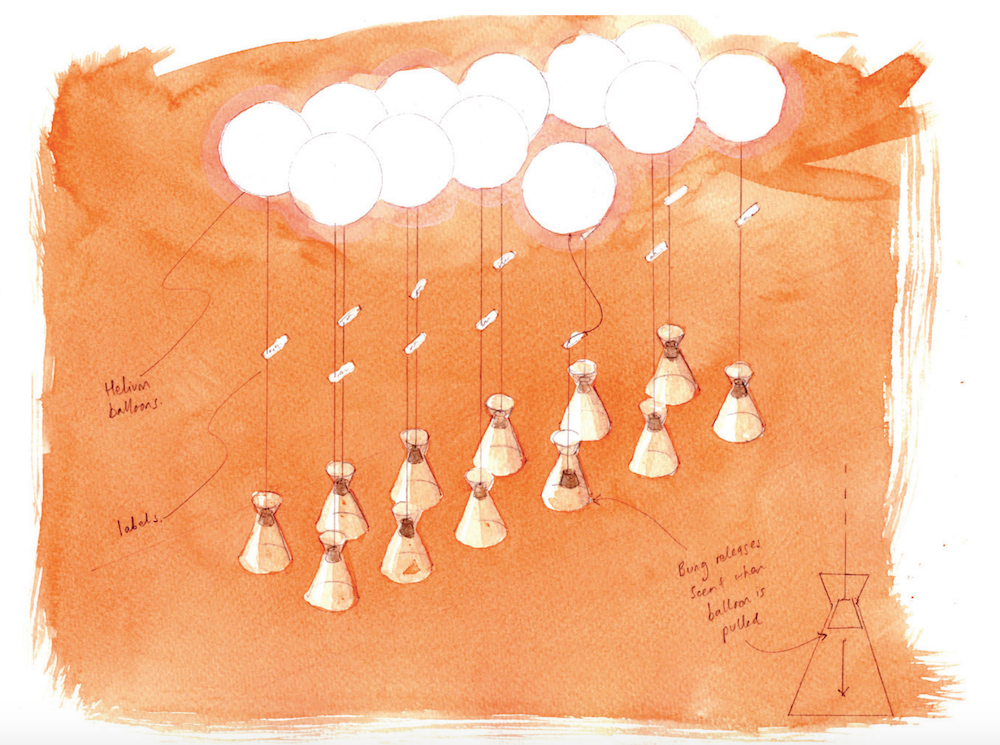

Yes, we were approached by the MUDAC (Musée de Design et d’Arts Appliqués Contemporains) in Lausanne to design the setting for a perfume exhibition. It was a rare commission, as we are not interior designers and the brief involved creating a display for something intangible, scents. But the result has a strong resonance on how me and Tim think and the work we like to do, this idea of making visible the invisible and capturing a fleeting moment.

We thought there were two ways of tackling the brief, one making it as physical as possible to counter the fact that the essence of the exhibition was intangible, and the other doing the opposite, that is, designing as little as possible to eco the invisible yet powerful presence of perfume. We opted for the latter, which was challenging, but for us was more coherent, working with light and glass, ephemerality and intangibility, rather than over-engineering it or over designing it. We were really lucky to have exceptional light in the museum, an amazing collection of glass and connections to local glass blowers, so the project developed organically.

How did the museum reach out to you?

The project came out from a workshop we gave in the framework of the Domaine du Boisbuchet summer programme. Normally we would set our own brief for the week-long workshop but on this occasion, Boisbuchet offered to us a set brief, which was to work with a museum that was planning a perfume exhibition.

The museum wanted us to try out how a perfume could be presented to people. We made our own perfumes using a similar harvesting technique to the one we used to create our herbarium based projects. We asked them to extract perfumes from the countryside. We added a ceramic and glass element to it. We also worked with glass blowers and we presented the results of the workshop creating the scenography for a performance with scents which was a huge success. The museum was happy with what resulted from our investigation in perfume and as a result, they asked us to work with them designing the space for the exhibition.

In 2010 you were part of the exhibition “Design by Performance” at Z33 House for Contemporary Art. In 2015 you took part in the Barbican performance exhibition Station to Station, and you collaborated with choreographers of the Siobhan Davies dance company. How do you approach performance from the perspective of design?

Normally, when we make something new we always focus just as much on the moment of creation as on the finished product. This way of thinking is linked to performance, to performing a process. Actually, our work is about this very moment, the moment when design products suddenly come to life. So you could say that they become something out of nothingness. We always try to find this moment in our work and show it to the spectators because for us it is where the beauty of the product is, not in the finished piece.

For Station to Station, we were paired with the Siobhan Davies dance company. They like working with artists. Together, we did a one-off performance in the Curve Gallery that had a lot to do with the technique of doing something, in this case, making lines in chalk and the body movements used to do that. For Design by Performance, we created what we called a Running Mould, an interpretation of the artisanal technique of making plaster cornices found in classical architecture. We build a pivot at the centre of the gallery and poured wet plaster on the floor. When the plaster was about to cure, we pushed a large wooden running mould with a sharp zinc profile through the paste-like material several times, building up layer after layer, to leave a perfect plaster scraping behind. After drying out completely, a hard plaster bench remained.

Domino light also requires a kind of performance…

Yes, all these projects you are focusing in have something in common, they reflect about something being there only for a moment, capturing the beauty of a flower in the Botanical tiles, trying to retain the molecules of perfume in Nez a Nez, re-enacting a gesture in Station to Station, reviving a classic artisanal technique with Running Mould or, like in Domino Light, showing that light is about a moment of conductivity, the moment when the electrical circuit is completed.

With Domingo Light, we wanted to make how the circuit works visible. Cooper has a conductive element, so we built domino pieces out of copper and only when the pieces touch each other and the circuit is completed, the light switches on. At the moment we are thinking about evolving the project. We love that element of performance with our projects.

Sarah, you are from the Netherlands and studied at Design Academy Eindhoven, which has an important design scene, but you met doing your MA at the Royal College of Art in London. How do you see both design scenes?

I might have come here because there is already an expansive design scene there and it’s not really the scene I am most comfortable in. We work within the field of design, but in the way we research and think we spread out, especially in the people we collaborate with: dancers, artists, perfumers, musicians, botanists, engineers, architects… You don’t travel very far by working with other designers, we have influences, but only those in very close proximity to us. We find the London scene much more experimental in a way, more free from trends.

You have presented ambitious installations at Milan Design Week, at the London Design Festival and the Biennale Internationale of Design in Saint-Étienne, and produced many complex projects and yet after 10 years you still keep a small studio practice. How do you manage the workload?

We’ve never really wanted to work very commercially. We wanted to be manoeuvrable and to work only in whatever we found creatively interesting to work in. We expand and contract our structure adjusting to the requirements of every project, and we (Tim and I) try to keep our artistic lead intact as much as possible. Our work is conceptual, and very much thought through. It is not always visible but we always spend a lot of time talking together before we do something. We write down the argumentations, for us it is really important to know why we are creating something. However, we have always worked with people and we are easily expandable when necessary.

What are you working on at the moment?

It’s funny because we are working on several projects at the moment, but actually, it was supposed to be a quiet time. We had planned to take a break to create space for new ideas but it’s not yet happening. We are working on a new collection for Gallery Fumi We have also taken a couple of commissions, one around the boundaries of things we have done and one that is completely new, and also, we are working on an installation for a spa. We haven’t done anything like that before, so it is quite exciting!

If you want to know more about the both aesthetically and conceptually fine work of Glithero, you can check out more of their projects on their website.

Interview by Sol Polo

Pictures courtesy of Glithero.