Rediscovering Frida Kahlo

ho

World experts in Frida Kahlo meet in London to share the knowledge generated by the discovery, in 2004, of the artist’s wardrobe.

On November 18th, the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London will close the doors of “Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up”, an exhibition that has caused a lot of expectation for showing, beyond her well-known art, the unique wardrobe and belongings of the artist, never before exhibited outside Mexico and discovered only 14 years ago, when a room that her partner, the artist Diego Rivera, had asked to keep sealed during the 50 years after the death of Kalho, was finally opened.

This unveiling of her wardrobe and belongings has been a revolution for scholars and Fridamaniacs around the world. Some of them met on November 2nd and 3rd, at the “Frida Kahlo: Inside and Outside” conference organized jointly by the V&A and University of the Arts London (UAL) around the exhibition, to share the knowledge generated by the study of these pieces and how they have contributed to understanding the complexities of the art and the figure of the artist. In this article, we review some details of the exhibition and the conference.

The Blue House

Frida lived all her life in the same house where she was born in 1907 and died in 1954, popularly known as The Blue House, which today houses the Frida Kahlo Museum. The father of Frida, Guillermo Kahlo – Hungarian-German by birth-, built it in 1904 in the style of the time: with a central courtyard with the rooms around it and a French style exterior. After the wedding of Frida and Diego in 1929, the two imbued a special character to the house with vibrant colours and popular Mexican decoration.

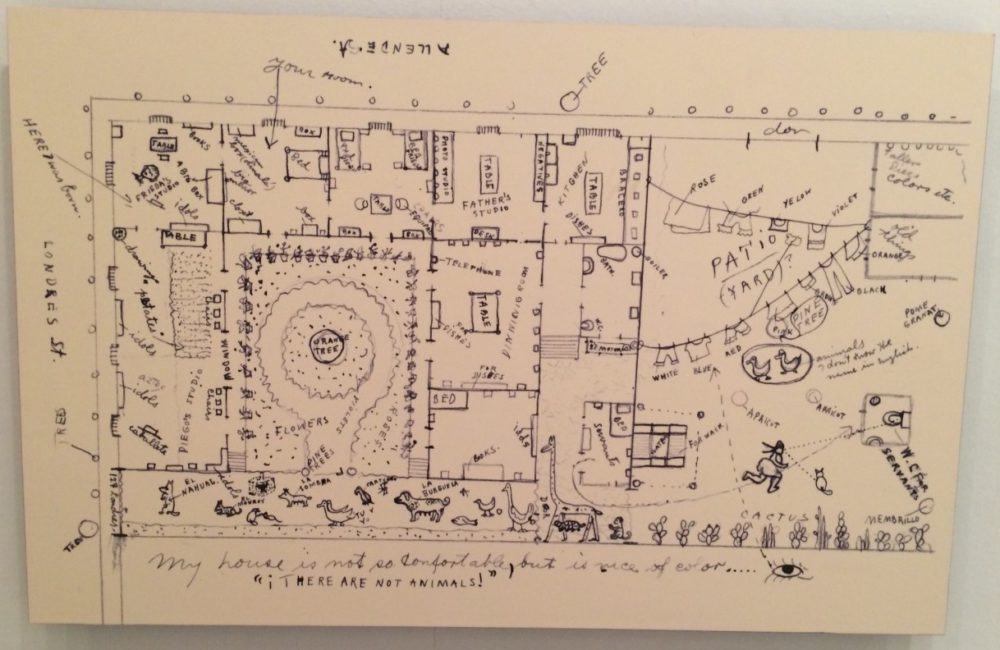

The house was the singular meeting point where the circle of intellectuals who surrounded the couple met, amongst them Trotsky and Maria Sedova, André Breton and Jacqueline Lamba, and artists such as Remedios Varo. But above all, it was the refuge and the epicentre of the artist’s creative activity, which began in the wake of the convalescence of the serious accident that broke her spine and pelvis in 1925. Besides the trips Kahlo made to the USA and Europe, mostly to accompany her husband or receive medical treatment, the artist always had a special bond with the house and this is shown by a map that she outlined with exquisite detail and that is part of the exhibition:

The voice of objects

Frida Kahlo’s legacy has been explored extensively from the point of view of her art and her relationships with other artists, but not so much from the point of view of her particular wardrobe and belongings, many of which remained closed for 50 years after her death in a room in her house by the will of her husband, the artist Diego Rivera.

The house museum Frida Kahlo proceeded to open this room in 2004 and with the advice of the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, they started the study, cataloguing, restoration and conservation of the more than 22000 pieces found. This project began to see the light in 2012 with the exhibition “Appearances can be deceiving: The wardrobe of Frida Kahlo”, co-curated by the Mexican Circe Henestrosa and the British Claire Wilcox. Six years later, some of these pieces have travelled from the street in the Mexican capital where Frida Kahlo’s Museum is located (London Street), to the real city of London, to present, for the first time outside of Mexico, the story of Frida Kahlo with fashion and design as protagonists.

Both “Appearances can be deceiving: The wardrobe of Frida Kahlo” and “Frida Kahlo: Making herself up” the title chosen for the Mexican iteration of the exhibition, propose a journey in which the voice of the artist is not articulated only through her art but mainly through the objects and architecture that the artist chose to live with: from The Blue House, to the beds where she recovered from her operations and where she began to paint, the ex-votos she collected, the shoes, corsets and prosthetics that she had to wear and the amount of traditional dresses, accessories and jewelry she used to wear.

Fashion as a cure

There has been a lot of talk about how Kahlo used art as an almost therapeutic means to convey the trauma caused by the accident she suffered at the age of 18, in which a tram ran over the bus in which she was travelling. What is less known is the severity of this accident, which fractured her spine by three points and perforated her pelvis. Kahlo could have been lying in a wheelchair all her life, but having overcome polio at the age of 6, she decided to fight to recover herself as much as possible through physical exercise and rehabilitation, and the help of multiple operations, corsets and eventually an orthopaedic leg when gangrene condemned her to an amputation. All her health problems were represented by the artist in her paintings, but in her day to day life, they went almost unnoticed because of the way she chose to live and dress.

Kahlo used fashion, like everyone else, to configure her appearance to her liking, and this meant hiding her “disabilities”. In the exhibition, you can see a selection of orthopaedic shoes with one heel higher than the other, along with personalized corsets that kept her column straight, and a wide selection of traditional costumes, huipiles, scarves, jewellery and headbands. The long skirts concealed her legs of different length and thickness, and eventually her prosthetic leg. The traditional huipil hid the lack of waist and chest that the corsets imposed on her torso, and her colourful jewellery, headbands and handkerchiefs gave a feminine air to her almost androgynous face.

In the conference organized around the exhibition, there was a lot of discussion about the problematics of the term disability. In a way, everyone has one disability or another, and certainly, Kahlo’s capabilities far outweighed her disabilities. A proof of that is the healthy image that she managed to project despite the inner hell she was going through and chose to manifest through her art. Regarding the taboo of disability, the participation of Sophie Oliveira and Celeste Dandeker-Arnold in the conference were highly motivational. Oliveira is a young British designer specializing in prosthetics, who showed many examples of her work, both of clients who choose realistic options and others who choose creative options to make themselves unique. Dandeker-Arnold is a dancer who, after suffering an accident on the stage that left her in a wheelchair, decided to create the first contemporary dance company with healthy dancers and dancers with mobility problems: Candoco. This project seeks to claim dance as a tool for the expression of the body, not only of the normative body but of any body.

The rejection of Surrealism

In 1938, André Breton visited Mexico invited by the National University, and because of his friendship with Diego Rivera, he stayed for four months at The Blue House. During this time, Breton developed a great interest in the art of Kalho, in which the theoretician saw many connections with the surrealist universe he was the pope of. This interest propelled the first exhibitions of the artist, with a large exhibition hosted at Julian Levy’s gallery in New York that kicked off her international projection. Nevertheless, Kahlo saw Surrealism as a manifestation of bourgeois art with foreign roots and rejected her connection with the movement repeatedly: “I did not know surrealism until André Breton told me about it (…) I have never painted my dreams, I paint my reality.”

In fact, as the writer Carlos Fuentes notes at the introduction of the printed edition of Frida’s diary, “what the French surrealists codified has always been a reality in Mexico and Latin America, part of the cultural current, a spontaneous fusion between myth and reality, sleep and vigil, reason and fantasy”. Proof of this is the work of Gabriel García Márquez and what has been identified as “magical realism”. In any case, the coexistence of the artist with the theorist and his wife, with whom she established a great friendship, is evident in works such as “El sueño” (The dream), or the exquisite corpse she created with Lucienne Block.

A visionary figure

It is quite remarkable how a figure like Kahlo’s, so brief and punished, so unattractive and traditional in appearance, can have such relevance today, 64 years after her death, but the truth is that, as the title from the Mexican exhibition preaches: appearances can be deceiving. Indeed, her superficial image was hiding a character with a great personality, culture, intelligence, sensitivity, strength and feminist vision.

As the Mexican fashion designer Carla Fernández recalled in the conference, Kahlo’s indigenous wardrobe not only hid her unfortunate legs but also highlighted the power of the matriarchy that created it, and the need to maintain modernity without conditioning tradition. This need is what governs the brand of Fernandez, who works with artisans from Mexico to preserve their techniques and update them to avoid their eventual disappearance.

In short, Kahlo was an example of struggle, a person who applied her revolutionary ideas in her day to day and fought against her body, against patriarchy and against social and artistic conventions. Her wardrobe and her way of life, interwoven with her art, make up a three-dimensional image of her universe, terrible and fantastic at the same time, or as André Breton described it in the essay of her first exhibition in New York: a bomb with a pink ribbon around it.

Author: Sol Polo